Steamed Buns, a Lesaffre Expertise

Like China itself, mantou has an age-old history steeped in legends and symbols and has evolved over time with the Chinese people

The history of mantou is closely linked with the Three Kingdoms Period (AD 220-280). Strategist, Zhu Geliang, is said to have led the armies of Shu in the south Campaign, and, after defeating King Meng Huo, he came across a fast-flowing river on his way back. Local barbarians told him that the river spirits could be appeased by the sacrifice of 50 men, each of whom would have their heads cut off and thrown into the river. Exhausted by the campaign and proud of the low number of casualties, Zhu Geliang therefore decided to fake the men’s heads by stuffing some dough balls with meat and throwing them into the river. As the waters of the river grew calm, he and his army were able to cross. The meat-filled dough balls thus became known as “Barbarian heads” or mantou in Chinese.

The first known uses of sodium bicarbonate in steamed buns date back to 1206. The steamed bun was the only type of bread eaten in Asia until 1866, the year in which the first European buns (mianbao 面包/麵包) were introduced into the country, mainly via Hong Kong and Guangzhou. In 1970 yeast was imported into the Guangzhou region for the first time to replace the traditional sourdough (laomian 老面/老麵). The first local yeast factory (Danbaoli 丹宝利/丹寶利) was built in Guangdong in 1985.

A product particularly well suited to Asia and its production, environment, and consumption demands

Historically and culturally, mantou is a staple in northern China, as a main source of protein, especially in the grain-producing Shandong province. The northern mantou is eaten with all 3 meals of the day. Consisting of only flour, water, and a fermentation agent (yeast or traditional sourdough), an alkali (baking soda, i.e. sodium bicarbonate) is often added to neutralize the pH created by the lactic ferments, to lessen the sour taste of the finished product. It is typically white, round, and ball- or cylinder-shaped, with a smooth, even surface. It has a dense, elastic, grainy texture and weighs between 50 and 150g.

The southern mantou is a traditional product (snack or dessert) that supplements rice, the main staple crop grown in southern China. The southern mantou often has a sweet taste, 5 to 20% sugar to the weight of flour, sometimes with a trace of salt and shortening, and is usually softer than its northern counterpart.

Mantou, in its northern and southern variations, belongs to the steamed bun family, which clearly differs from other western bread families in its production method and in the end-product itself: steaming (at high humidity and a temperature of no more than 100°C) does not allow browning or the release of associated aromas to occur, since the temperature required to generate the famous Maillard reactions and caramelization is never reached. Unlike European bread, mantou has no crust or experience a loss of weight through evaporation during baking. The resultant steamed bun is soft, smooth and white.

Mantou is eaten hot, after steaming or reheating, in individual portions. The main evaluation criteria are as follows:

- Appearance: must be smooth and even, white in the north, a slightly creamy color in the south, shiny, consistent (i.e. symmetrical, not wrinkled, blistered, or patchy).

- Texture: should be dense in the northern mantou, slightly more aerated in the southern version. The crumb should be fine, consistent, elastic, chewy (not sticky), and more aerated in the south.

- Aroma and taste: these should be natural, if not neutral (especially in the case of the northern mantou), expressing the ingredients used for the dough or the fillings; the fillings can be sweet (azuki bean, custard cream, black sesame seeds) or savory (vegetables, meat, seafood).

A simple recipe, but a high-tech product

The basic ingredients for a mantou are flour, water, and a fermentation agent. These may be enriched with sugar, salt, and shortening for the southern mantou (nanfang mantou), and even stuffed (many types according to a secret recipe) in the case of the baotzi (包子).

The flour used is always a wheat flour with a low ash content (0.35 to 0.55%) and thereby results in a white color with no speckling. The protein level is medium to low with a consistency profile yielding an elastic dough (little or no extensibility) with high tenacity. The flour is increasingly corrected to guarantee constant regularity, despite the ever-changing grain quality, and to make it especially suited to mantou production (machinability and impact on finished product). The falling number (FN) is often over 300 and the damaged starch rate is below 8% (in excess, it can result in stickiness and speed up starch retrogradation). Moisture content is quite low at around 40 to 55%, depending on the flour (protein level, damaged starch content). The dough is therefore stiff and the lamination stage is crucial in the dough’s development.

The fermentation agent can be sourdough or yeast (or indeed both, as in a yeast-based dough left to rest and ferment for a day or more). The traditional fermentation agent is laomian, which is often prepared in a liquid form based on rice or fruit; the micro- organism fermentation culture is mainly wild yeasts and lactic bacteria, hence the high acidity of the dough created during the process. In order to neutralize the low pH, baking soda or a similar alkali is commonly added in moderate doses to prevent yellowing and a strong soda flavor. Yeast tends to replace these sourdoughs for its ability to control activity and taste and make the end product more consistent. Compressed yeast or instant dry yeast can be used, with a low-sugar profile being common in the northern mantou and a high- sugar profile in the sweet mantou and baotzi.

- Other raising agents can include: baking powder for obtaining “oven spring.”

- Other ingredients include: salt for taste and shelf-life, sugar for taste and texture, shortening for taste, as well as texture and shelf-life.

- Improvers/correctors can include: oxidants (generally ascorbic acid); enzymes for the consistency, machinability, gas retention and finished characteristics, such as volume and texture; emulsifiers for gas retention, texture and shelf-life; and preservatives.

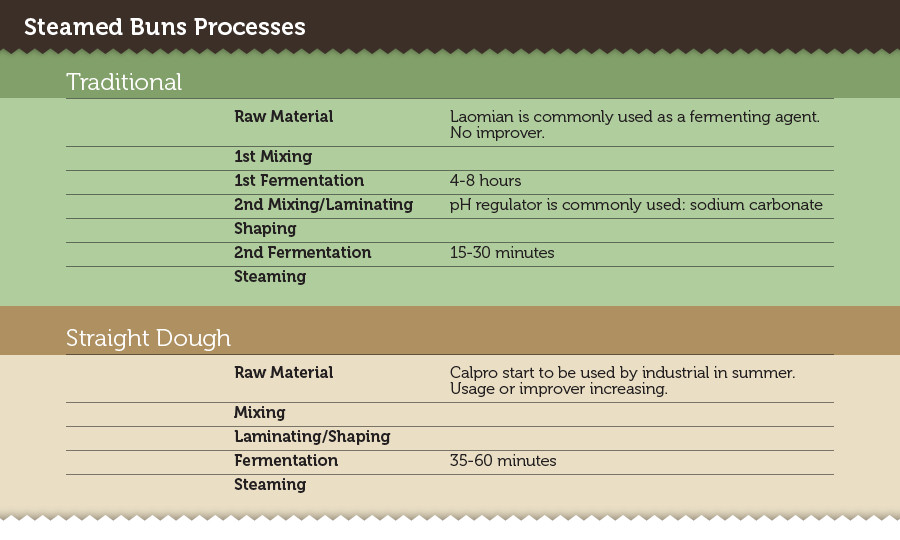

A traditional, yet increasingly controlled process

There are two ways of making steamed buns: the traditional way and the direct method. The traditional method aims to develop the aroma, limit the use of yeast, improve dough working and the finished product characteristics by means of a long process (and often not easily reproducible). An initial dough is made with yeast and incorporated after a day of “free” fermentation into another dough (10 to 50%), often the main dough of the day before. Another method would be to make a starter culture, which is refreshed several times in order to increase the bacteria population, then incorporated into the main dough (this kind of sourdough is called laomian).

The direct method is based on a much shorter process (1 to 3 hours) with the use of yeast and allows better control over taste consistency and fermentation activity. It yields a better-looking and more consistent end product, but also gives a more neutral taste and a shorter shelf-life. This method is widely used in automated production, which has boomed in recent years.

The automation of production methods goes hand-in-hand with the increasing requirements governing raw materials: more specific flours (grinding process, flour blends, flour improvers), yeast with very constant performance and stability over time, and specially formulated improvers. Automation, reduced production time and the increase in hourly volume all make higher demands on raw materials in order to prevent variations on the production line at inspection points. Meanwhile, equipment has also changed enormously. It started out by reproducing human gestures, but is now more specific, offering line laminating, continuous filling, automated tray loading, etc. The concentration of production sites has also meant that products must have a longer shelf-life and to be able to travel longer distances, in order to reach catchment areas and meet distribution demands. Freezing technology and new packaging techniques (i.e. modified atmosphere) have also contributed a great deal to these developments.

Using either method, the products can then be sold directly (after steaming), kept hot and moist inside bamboo boxes with steam generated from below, and kept fresh to be subsequently reheated, or frozen (after being fully steamed).

Mantou, a product of the past with a great future

Culturally, mantou is a product that has enjoyed a long and rich history, yet it has a bright future ahead of it due to the following:

- Nutritional value: rich in slow-burning carbohydrates, contains a fair amount of proteins, low lipid content; it is also a source of some vitamins and minerals.

- Presentation: adapted to the increasingly nomadic working lives of people looking for a ready-to-eat product (no equipment, no cutlery or other constraints), pre-packed in individual portions, easy to personalize (shaping and filling), easily accessible (mantou makers are popping up everywhere), very fresh.

- Production method: enables the concept to be adapted to ‘hot corners’ thanks to centralized production: concentration of human, technical and financial resources on the same site, with easy access to transportation. The products are then extra fresh all day long, easily reheated and losses due to unsold products are limited. These spots are typically small: minimal or no storage area, no need for heavy goods vehicle access, power, and safety constraints (baking).