Taste of Bread: About the Word Taste

How much simpler it would be for bakers if consumers unanimously agreed that their bread had a really good taste. Unfortunately, individuals judge for themselves what is good and what is bad. Considering the diversity of bread throughout the world, it is easy to see why appreciation criteria vary from one culture to another and according to individual tastes! How can one explain the taste of bread? What mechanisms are at work in the consumer’s brain? Our discussions with semiologist Laurent Aron give some useful information for understanding this word which is present in everyone’s mouth.

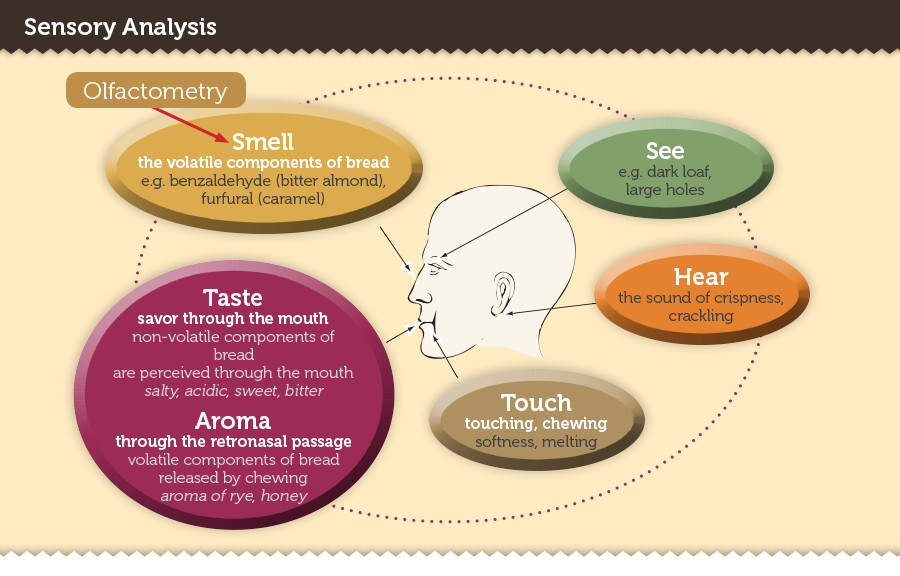

The brain, in a way, is at the core of taste because it concentrates the various sensory experiences. But how do they get there? Try an experiment: put a piece of bread on your tongue, and your tongue and nose go into action immediately. Both these oral-nasal organs are receptors of sensory information. Firstly, the taste buds spread all over the tongue recognize a series of flavors: sugar, salt, acidity and bitterness among many others. At the same time, the nose sends complementary information to the brain as the aromas are exhaled through the mouth and penetrate the retronasal passage. This combination of tastes and aromas is called “flavor.” The consumer can also experience a food differently according to various aesthetic sensations. For example, a food eaten hot does not have the same taste as when eaten cold. Melting vanilla ice cream tastes sweeter than when it is eaten very cold. Finally, there are physical perceptions, such as whether a food is crispy or soft. When talking about chocolate, one often mentions its crunchiness as a taste criteria.

Taste is so complex that it makes use of all five senses: smell, touch, sight and sound as well as taste itself. This restrictive classification goes back over 2500 years to Aristotle, who gave himself the task of arranging everything – men, flora, and fauna – into a precise register with tangible reference points. But does this arrangement really help to explain the mechanics of taste as it is understood today? Haven’t some senses – such as the sense of balance – been left out of this classification?

Social and Cultural Values

The brain keeps a personal record of products we consume, together with the level of pleasure we experience from them. For example, some clients think a baguette with pointed ends is better than the same baguette without pointed ends. Appearance influences our senses, as does the packaging of the product. Isn’t it a real pleasure to go into a bakery where the decor, the smell, and the bread’s display stirs the senses and make customers dream?

It awakens childhood memories and represents the epitome of a healthy, well-made, traditional product. Sensory panels try to understand this phenomenon by starting with the simple statements “I like it” or “I don’t like it” and then trying to interpret the reasons that lead to this feeling. This is where individual choice is important. Ideas evolve and sometimes we can help to change values. Twenty years ago, white bread was highly thought of, but these days it is rejected if it is too white. The reason for this lies in the cultural associations of the product. In the period from the fifties to the seventies, white bread required manual sifting of the flour. As technology has gradually replaced manpower, we now tend to look for “unrefined” products, synonymous with authenticity, unaltered by science or machines. A similar situation exists in the sugar industry where refined white sugar now has less added value than brown sugar.

Figure 1: Taste is a complex mechanism based on the five senses

The limitations of the language of bread

It is difficult to find a word for every sensory perception. It is perhaps impossible, as individuals have their own words, their own vocabulary and above all, their own way of seeing things. Words are enriched by experience, exactly like colors. When we are young, we discover primary colors like blue, then as we grow older we fill in the palette by adding shades with names like ultramarine and indigo. We use a standard shade card as a tool to establish definitions of color, but it is a matter of interpretative understanding rather than of absolutes. Likewise, in the language of bread, there is no supreme taste or absolute palate. Interpretation often translates into a profusion of words as a means of expressing ourselves and of having the pleasure of speaking about something and sharing our experiences with others, even if individual opinions differ. The language used to describe the taste of bread is often constructed by borrowing pseudo descriptions from different imaginary universes. In the bread world, these descriptions can refer to places, or more often to processes and actual ingredients such as flour, or supposed ingredients such as nuts.

The taste of bread is a culture in progress to which words are freely added. The vocabulary grows, enriched by experience. In contrast, the lexicon of sensory analysis is created through a process where words to identify tastes are selected from a palette of terms agreed by all. In doing so, we move voluntarily from a language that is rich and abundant to one that is restrained. Camille Dupuy, who is in charge of sensory analysis, explains, “At Lesaffre, we have established a precise lexicon for the sensory analysis of several clearly defined types of bread to give us clearer distinction in our classifications.”